First of all, the Index of Forbidden Books was established in 1543, so a council in 1229 could not have placed a book on it. Second of all, there has never been a church council held in Valencia, Spain. Plus, the Moors were in control of that area in 1229, so the Church could not have had a council there even if they wanted to.

There was a council in 1229, but it was in Toulouse, France. It was a local council, not an ecumenical council (which means it did not represent the entire Church). This council did deal with the Bible, in a way. It was called to deal with the Albigensian heresy, which maintained that the flesh is evil and therefore marriage is evil, fornication is not a sin, and suicide is not immoral. They also opposed taking oaths, which completely undermined medieval feudal society, which was based on oaths. These Albigensians were using corrupt vernacular versions of the Bible to support their theories, twisting the Bible to “prove” their point. To combat this, the bishops at Toulouse restricted the use of the Bible until this heresy was ended. This was a local restriction, not a universal one, and when the heresy was over, the restriction was lifted.

This restriction never affected more than one area of southern France, and is a far cry from the Catholic Church banning the Bible from all laymen.

The Index never included the Bible itself. Rather, specific editions and translations that had been altered, doctored, or or were an exceptionally poor translation.

The church banned un-approved translations that were defective .... why would the church want to allow faulty translations be provided to the faithful ?...

Would you allow your family whom you love to use a Jehovah's Witness Bible for their study? I think not. Then the same thing is true of the church in dealing with gross errors in vernacular translations.

Bible-reading in the ‘Dark Ages’ ?!?

some may say: 'Yes, they copied the Scripture, these monks and priests, but that was all; they did not know anything really about it, did not understand it; their work was merely mechanical.' Now, I shall show that the very contrary was the fact; they had a profound knowledge and understanding of the Bible, and it was their constant companion. (I) In the first place, the Bishops and Abbots required all their priests to know the Scriptures. We find constantly in the old Constitutions and Canons of different dioceses that the clergy were bound to know the Psalms, the Epistles, and Gospels, besides, of course, the Missal and other Church service books, (take for example, the Constitutions of Belfric or of Soissons). And these rules were effective; they had to be observed, for we find Councils like that of Toledo, for instance (in 835), issuing decrees that Bishops were bound to enquire throughout their dioceses whether the clergy were sufficiently instructed in the Scripture. In some cases they were obliged to know by heart not only the whole Psalter, but (as under the rule of St. Pachomius) the New Testament as well. I suppose most ministers of the Kirk could stand this test quite easily.

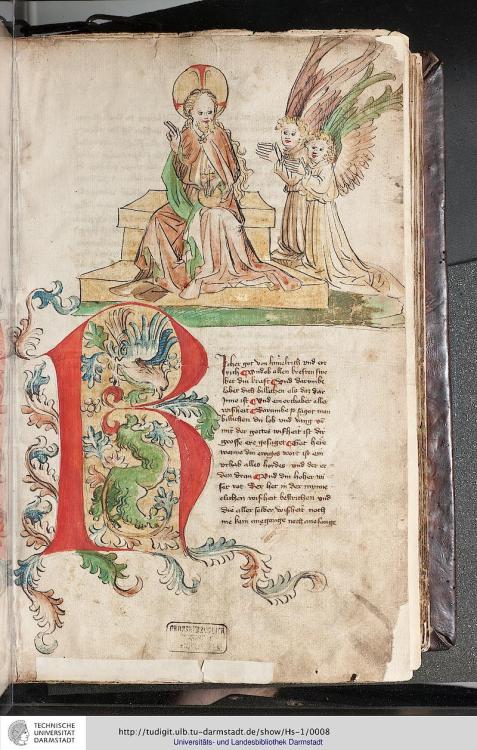

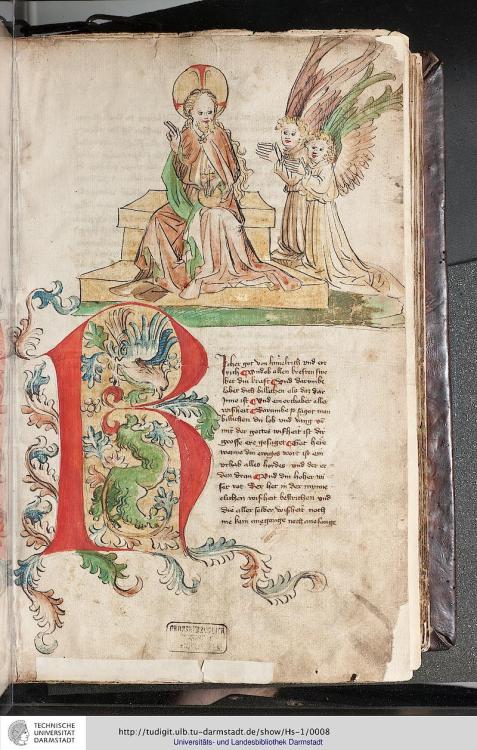

picture from 'Our Bible & the Ancient Manuscripts' by Sir Frederick Kenyon

http://medievalwriting.50megs.com/scripts/examples/smallgothic.htm#picture

Switzerland

Einsiedeln · 12th century

Around 850-872 "Kleinen Hartmut-Bibel"

Picture :

Bible manuscript from the time of Hartmut, Vice-abbot ca. 850-872 and Abbot 872-883

and there are Numeros other German Bibel Tests from Between 800 and the late middel ages in this Library. Link : Codices Electronici Sangallenses.

The Lindau Gospel Book Cover is a signatory representative of the early and mid 9th century due to its quality to compel and garner admiration from the common masses. The cover exemplifies the attributes of many other works from its period.

Though the type of visual representation found in the Psalter are thought to be modeled after earlier forms there is a certain simplicity in style that seems to compel not the courtesans, but the common citizen . The images are highly stylized, a far cry from the art of the aristocracy; even more telling, it was rendered in the very local artistic style of the workshops of Reims. The drawings are impressionistic and worked as a puzzle for the viewer. There was a definite link reaching out from the work to the viewer, the Psalter served as a prototypical way of engaging the audience in a visual tale while communicating the literal story behind it. The viewer was able to take a mental picture of a liturgical event.

Original book can be seen here: http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fmdz10.bib-bvb.de%2F~db%2Fmets%2Fbsb00023847_mets.xml

more discussions on this topic you can find here:

http://forums.catholic.com/showthread.php?t=272675

I think I hear the voice of the objector, who will not believe all this if he can possibly help it—'Yes; well, perhaps the clergy did know the Bible, but nobody else did; it was a closed and sealed volume to the poor lay people, because, of course, it was all in Latin.' Now, leaving aside the question of Latin for a moment (for I shall come back to that immediately), it is utterly false to say or suppose that the lay folks were ignorant of the Scriptures. They were thoroughly well-acquainted with them so far as they required to be in their state of life. It is true, of course—and how could it be otherwise?—that ecclesiastics being the reading men and writing men, in short, the only well-educated persons of those days, naturally have left behind them more evidence than most lay people could do of their familiarity with the Sacred Word; but it is yet the fact that the literature of those ages, outside clerical documents altogether, which has come down to us, is steeped and permeated through and through with Scripture. Conversations, for example, correspondence, law deeds, household books, legal documents, historical narratives—all are full of it; full not only of the ideas, but often of the very words of Scripture. How many lawyers and doctors and professors and ordinary lay folks nowadays, I wonder, would be found quoting from the Bible in their writings?

They all knew it and understood it, and enjoyed the numberless quotations and references to it in sermons and addresses, and could often repeat portions of it from memory. 'The writings of the dark ages'—says Dr. Maitland in chapter 27 of his most valuable and entertaining book, The Dark Ages—'the writings of the dark ages are, if I may use the expression, made of the Scriptures. I do not merely mean that the writers constantly quoted the Scriptures, and appealed to them as authorities on all occasions as other writers have done since their day; but I mean that they thought and spoke and wrote the thoughts and words and phrases of the Bible, and that they did this constantly and habitually as the natural mode of expressing themselves.

But how, it may be asked, could the people who were unable to read (and they were admittedly a large number) become acquainted with the Bible? The answer is simple. They were taught by monk and priest, both in church and school, through sermon and instruction. They were taught by sacred plays or dramas, which represented visibly to them the principal facts of sacred history, like the Passion Play of today at Oberammergau. They were taught through paintings and statuary and frescoes in the churches, which portrayed before their eyes the doctrines of the Faith and the truths of Scripture: and hence it is that in Catholic countries the walls of churches and monasteries and convents, and even cemeteries, are covered with pictures representing Scriptural scenes.

Vast numbers could not read; I admit it; the Church was not to blame for that. Latin was the universal tongue, and you had to be rather scholarly to read it. But I protest against the outrageous notion that a man cannot know the Bible unless he can read it. Can he not see it represented before his eyes? Can he not hear it read? Do you not know and understand one of Shakespeare's plays much better by seeing it acted on the stage than by reading it out of a book? Do the visitors to Oberammergau, witnessing the 'Passion Play', not come to understand and realise the story of the Passion and Death of Our Lord more vividly byseeing it enacted before their eyes than if they read the cold print of a New Testament?

England:

Abundance of Vernacular Scriptures before Wycliff

I HAVE said that people who could read at all in the Middle Ages could read Latin: hence there was little need for the Church to issue the Scriptures in any other language. But as a matter of fact she did in many countries put the Scriptures in the hands of her children in their own tongue. (I) We know from history that there were popular translations of the Bible and Gospels in Spanish, Italian, Danish, French, Norwegian, Polish, Bohemian and Hungarian for the Catholics of those lands before the days of printing, but we shall confine ourselves to England, so as to refute once more the common fallacy that John Wycliff was the first to place an English translation of the Scriptures in the hands of the English people in 1382.

Yet we may safely assert, and we can prove, that there were actually in existence among the people many copies of the Scriptures in the English tongue of that day. To begin far back, we have a copy of the work of Caedmon, a monk of Whitby, in the end of the seventh century, consisting of great portions of the Bible in the common tongue. In the next century we have the well-known translations of Venerable Bede, a monk of Jarrow, who died whilst busy with the Gospel of St. John. In the same (eighth) century we have the copies of Eadhelm, Bishop of Sherborne; of Guthlac, a hermit near Peterborough; and of Egbert, Bishop of Holy Island; these were all in Saxon, the language understood and spoken by the Christians of that time. Coming down a little later, we have the free translations of King Alfred the Great who was working at the Psalms when he died, and of Aelfric, Archbishop of Canterbury; as well as popular renderings of Holy Scripture like the Book of Durham, and the Rushworth Gloss and others that have survived the wreck of ages. After the Norman conquest in 1066, Anglo-Norman or Middle-English became the language of England, and consequently the next translations of the Bible we meet with are in that tongue. There are several specimens still known, such as the paraphrase of Orm (about 1150) and the Salus Animae (1050), the translations of William Shoreham and Richard Rolle, hermit of Hampole (died 1349). I say advisedly 'specimens' for those that have come down to us are merely indications of a much greater number that once existed, but afterwards perished.

The translators of the Authorised Version, in their 'Preface', referring to previous translations of the Scriptures into the language of the people, make the following important statements.

'The godly-learned were not content to have the Scriptures in the language which themselves understood, Greek and Latin ... but also for the behoof and edifying of the unlearned which hungered and thirsted after righteousness, and had souls to be saved as well as they, they provided translations into the Vulgar for their countrymen, insomuch that most nations under Heaven did shortly after their conversion hear Christ speaking unto them in their Mother tongue, not by the voice of their minister only but also by the written word translated.'

Where We Got the Bible: Our Debt to the Catholic Church

by The Right Rev. HENRY G. GRAHAM,

http://www.catholicapologetics.info/apologetics/protestantism/wbible.htm#CHAPTER IX

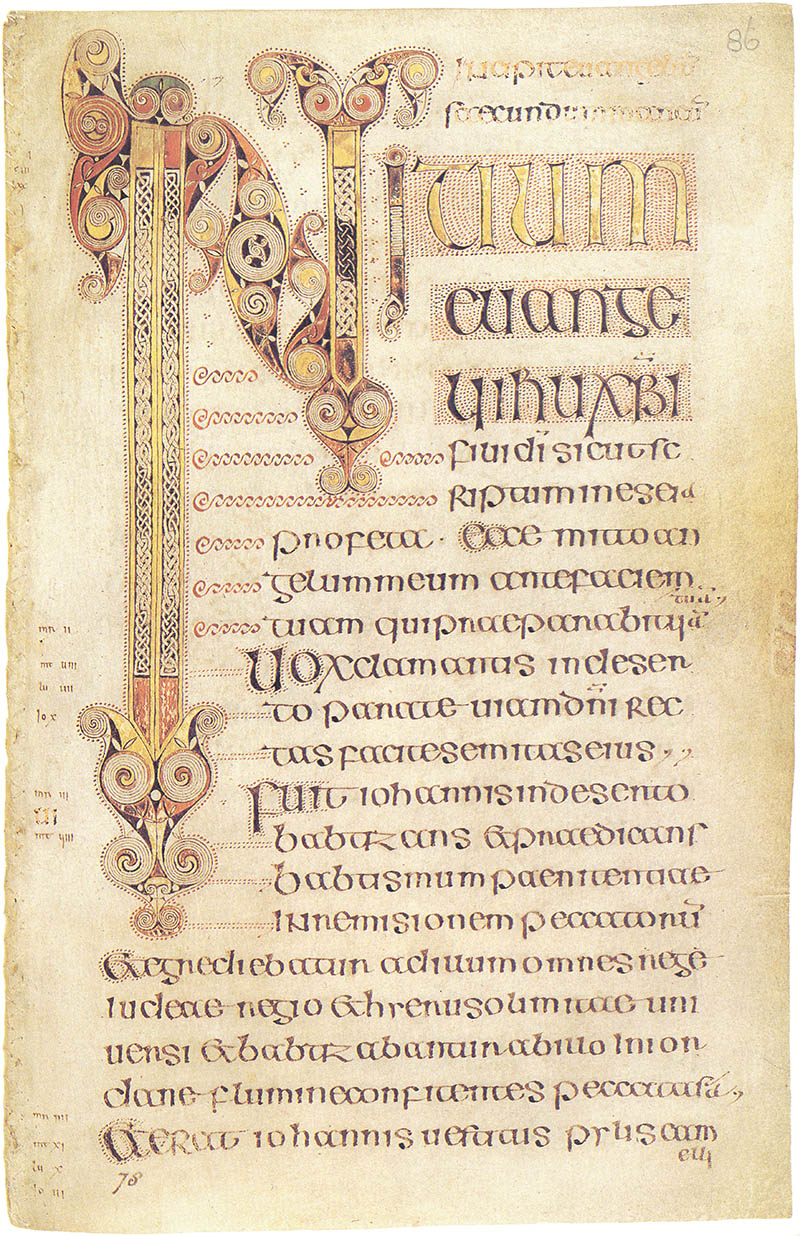

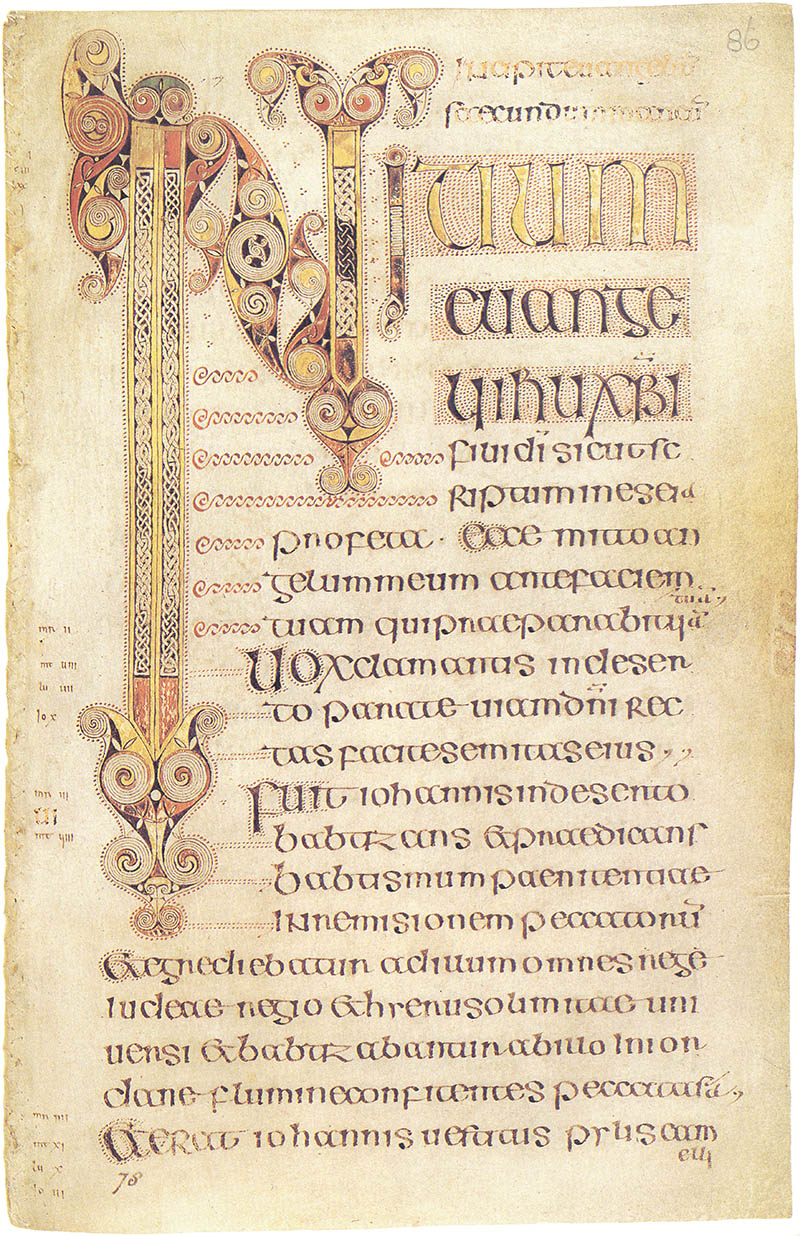

THE LINDISFARNE GOSPEL

"The Venerable Bede Translates John"

Doctor of the Church, Monk, Historian

Born ca. 673

near Sunderland

Died 26 May 735

Jarrow, Northumbria

Honored in Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, Lutheran Church

THE LINDISFARNE GOSPEL

circa 690 AD

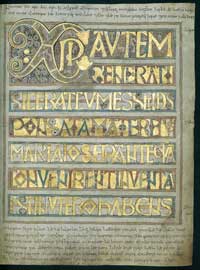

ENGLISH GOSPEL - 12th century

picture from 'Our Bible & the Ancient Manuscripts' by Sir Frederick Kenyon

where in the the Ormulum was written.

. (12 th century )

some Gotic example of the Bibel you can find here; http://medievalwriting.50megs.com/scripts/examples/smallgothic.htm#picture

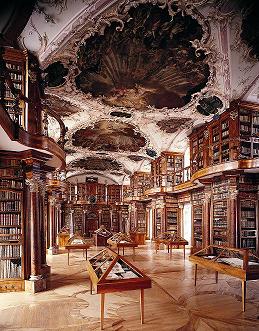

Switzerland

The Benedictine Abbey of St. Gall, Switzerland, is founded on a site that had been used for religious purposes since 613.

"Around 613 an Irishman named Gallus, a disciple and companion of Saint Columbanus, established a hermitage on the site that would become the Abbey. He lived in his cell until his death in 646.

"Following Gallus' death, Charles Martel appointed Othmar as a custodian of St Gall's relics. During the reign of Pepin the Short, in 719, Othmar founded the Abbey of St. Gall, where arts, letters and sciences flourished. Under Abbot Waldo of Reichenau (740-814) copying of manuscripts was undertaken and a famous library was gathered. Numerous Anglo-Saxonand Irish monks came to copy manuscripts. At Charlemagne's request Pope Adrian I sent distinguished chanters from Rome, who propagated the use of the Gregorian chant.

During the 9th Century a new, larger church was built and the library was expanded. Manuscripts on a wide variety of topics were purchased by the Abbey and copies were made. Over 400 manuscripts from this time have survived and are still in the library today" (Wikipedia article on Abbey of St. Gall, accessed 01-17-2009).

The Abbey contains one of the oldest, largest and most significant medieval libraries, consisting of 2100 codices. It is the only major medieval convent library still standing in its original location. 400 of the codices in this library date before 1000 CE. These manuscripts are being made available on the Internet in a virtual library, the Codices Electronici Sangallenses.

for example

| Manuscript title: | Translatio barbarica psalterii Notkeri tertii (Old High German Psalter by Notker the German) |

Around 850-872 "Kleinen Hartmut-Bibel"

Picture :

Bible manuscript from the time of Hartmut, Vice-abbot ca. 850-872 and Abbot 872-883

and there are Numeros other German Bibel Tests from Between 800 and the late middel ages in this Library. Link : Codices Electronici Sangallenses.

The Book of DimmaCirca 750

The Book of Dimma, an 8th century Irish pocket Gospel Book signed by its scribe, Dimma MacNathi, at the end of each of the Four Gospels, originated from the Abbey of Roscrea, founded by St. Cronan in County Tipperary, Ireland. "Dimma has been traditionally identified with theDimma, who was later Bishop of Connor, mentioned by Pope John IV in a letter on Pelagianismin 640. This identification, however, cannot be sustained. The illumination of the manuscript is limited to illuminated initials, three Evangelist portrait pages and one page with an Evangelist's symbol. In the 12th century the manuscript was encased in a richly gilt case" (quoted from the Wikipedia article on the Book of Dimma, accessed 11-22-2008)

The Book of Dimma is preserved at Trinity College, Dublin.

The Stockholm Codex Aureus, Looted Twice by VikingsCirca 750

The Stockholm Codex Aureus (also known as the "Codex Aureus of Canterbury") was produced inthe mid-eighth century in Southumbria, probably in Canterbury, England.

"The codex is richly decorated, with vellum leaves that alternately are dyed and undyed, the purple-dyed leaves written with gold, silver, and white pigment, the undyed ones with blackink and red pigment. The style is a blend of that of Insular art . . . and Continental art of the period.

"In the ninth century it was stolen by the Vikings and Aldormen Aelfred had to pay a ransom to get it back. Above and below the Latin text of the Gospel of St. Matthew is an addedinscription in Old English recording how, a hundred years later, the manuscript was ransomed from a Viking army who had stolen it on one of their raids in Kent by Alfred, ealdorman of Surrey, and his wife Wærburh and given to Christ Church, Canterbury" (Wikipedia article on Stockholm Codex Aureus, accessed 06-25-2009).

+ In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ. I, Earl Alfred, and my wife Werburg procured this book from the heathen invading army with our own money; the purchase was made with pure gold. And we did that for the love of God and for the benefit of our souls, and because neither of us wanted these holy works to remain any longer in heathen hands. And now we wish to present them to Christ Church to God's praise and glory and honour, and as thanksgiving for his sufferings, and for the use of the religious community which glorifies God daily in Christ Church; in order that they should be read aloud every month for Alfred and for Werburg and for Alhthryth, for the eternal salvation of their souls, as long as God decrees that Christianity should survive in that place. And also I, Earl Alfred, and Werburg beg and entreat in the name of Almighty God and of all his saints that no man should be so presumptuous as to give away or remove these holy works from Christ Church as long as Christianity survives there.

Alfred

Werburg

Alhthryth their daughter

The manuscript remained at Canterbury until the 16th century when it travelled to Spain. In 1690 it was bought for the Swedish Royal Collection, It is preserved in the Royal Library, Stockholm (MS A. 135).

Lindau Gospel Book Cover:

The Lindau Gospel Book Cover is a signatory representative of the early and mid 9th century due to its quality to compel and garner admiration from the common masses. The cover exemplifies the attributes of many other works from its period.

Though the type of visual representation found in the Psalter are thought to be modeled after earlier forms there is a certain simplicity in style that seems to compel not the courtesans, but the common citizen . The images are highly stylized, a far cry from the art of the aristocracy; even more telling, it was rendered in the very local artistic style of the workshops of Reims. The drawings are impressionistic and worked as a puzzle for the viewer. There was a definite link reaching out from the work to the viewer, the Psalter served as a prototypical way of engaging the audience in a visual tale while communicating the literal story behind it. The viewer was able to take a mental picture of a liturgical event.

Book of Durrow. The earliest surviving Gospel Book with a full programme of decoration (though not all has survived): six extant carpet pages, a full-page miniature of the four evangelist's symbols, four full-page miniatures of the evangelists' symbols, four pages with very large initials, and decorated text on other pages. Many minor initial groups are decorated. Its date and place of origin remain subjects of debate, with 650–690 and Durrow in Ireland, Iona or Lindisfarne being the normal contenders. The influences on the decoration are also highly controversial, especially regarding Coptic or other Near Eastern influence.[36]

After large initials the following letters on the same line, or for some lines beyond, continue to be decorated at a smaller size. Dots round the outside of large initials are much used. The figures are highly stylised, and some pages use Germanic interlaced animal ornament, whilst others use the full repertoire of Celtic geometric spirals. Each page uses a different and coherent set of decorative motifs. Only four colours are used, but the viewer is hardly conscious of any limitation from this. All the elements of Insular manuscript style are already in place. The execution, though of high quality, is not as refined as in the best later books, nor is the scale of detail as small.[37]

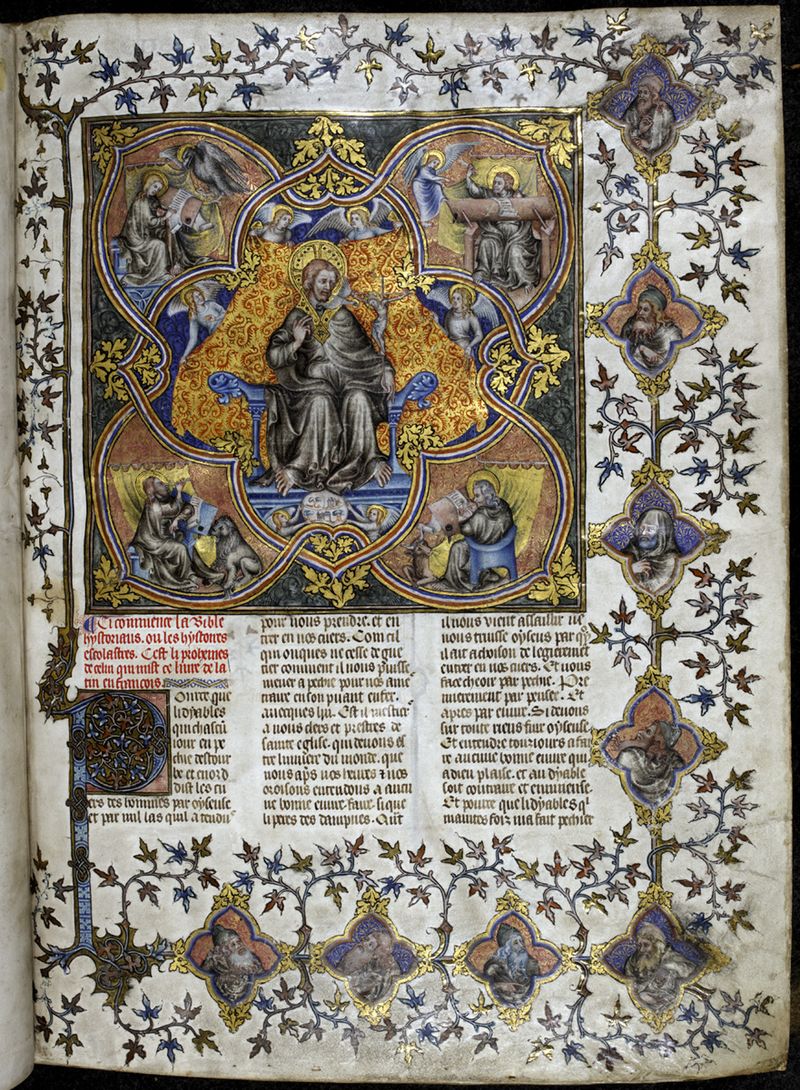

Bible historiale

Paris, 1356

The most common version of the Bible in French is known as the Bible historiale or history Bible, because it combines sections of the Latin Vulgate with commentary or gloss interpreting the biblical text .

The first complete Catalan bible translation was produced by the Catholic Church, between 1287 and 1290. It was entrusted to Jaume de Montjuich by Alfonso II of Aragon. Remains of this version can be found in Paris (Bibliothèque Nationale). Also, in the same French library, we can find another translation into Catalan, which Jaume II of Aragon received on November 23, 1319.

In the early fifteenth century appeared another whole Bible translation by Bonifaci Ferrer. In 1490 a psalter by Joan Roís de Corella came to light in Venice.

So there where plenty of Bibels in Vernacular language available, before

Martin Luther. As i have shown already in "Was Martin Luther really the First to translated the Bibel into the German Vernacular ?"

Now, how exactly did Martin Luther actually view the Bibel ?

This seem a rather Interesting topic as well.

This seem a rather Interesting topic as well.

Sola Scriptura or Prima Luther:

Although Martin Luther stated that he looked upon the Bible "as if God Himself spoke therein" he also stated:

My word is the word of Christ; my mouth is the mouth of Christ" (O'Hare PF. The Facts About Luther, 1916--1987 reprint ed., pp. 203-204).

Martin Luther Added to the Book of Romans

The Bible, in Romans 3:28, states,

Therefore we conclude that a man is justified by faith apart from the deeds of the law.

Martin Luther, in his German translation of the Bible, specifically added the word "allein" (English 'alone') to Romans 3:28-a word that is not in the original Greek. Notice what Protestant scholars have admitted:

...Martin Luther would once again emphasize...that we are "justified by faith alone", apart from the works of the Law" (Rom. 3:28), adding the German word allein ("alone") in his translation of the Greek text. There is certainly a trace of Marcion in Luther's move (Brown HOJ. Heresies: Heresy and Orthodoxy in the History of the Church. Hendrickson Publishers, Peabody (MA), 1988, pp. 64-65).

Furthermore, Martin Luther himself reportedly said,

You tell me what a great fuss the Papists are making because the word alone in not in the text of Paul…say right out to him: 'Dr. Martin Luther will have it so,'…I will have it so, and I order it to be so, and my will is reason enough. I know very well that the word 'alone' is not in the Latin or the Greek text (Stoddard J. Rebuilding a Lost Faith. 1922, pp. 101-102; see also Luther M. Amic. Discussion, 1, 127).

This passage strongly suggests that Martin Luther viewed his opinions, and not the actual Bible as the primary authority. By "papists" he is condemning Roman Catholics, but is needs to be understood that Protestant scholars (like HOJ Brown) also realize that Martin Luther changed that scripture.

Martin Luther, for example, taught,

Be a sinner, and sin boldly, but believe more boldly still. Sin shall not drag us away from Him, even should we commit fornication or murder thousands and thousands of times a day (Luther, M. Letter of August 1, 1521 as quoted in Stoddard, p.93).

He seemed to overlook what the Book of Hebrews taught:

The Bible, in Acts 19:18, states,For if we sin willfully after we have received the knowledge of the truth, there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins, but a certain fearful expectation of judgment, and fiery indignation which will devour the adversaries (Hebrews 10:26-27).

"And many who had believed came confessing and telling their deeds..."Yet Martin Luther rendered it, "they acknowledged the miracles of the Apostles" (O'Hare, p. 201).He also wrote,

St. James' epistle is really an epistle of straw…for it has nothing of the nature of the gospel about it" (Luther, M. Preface to the New Testament, 1546).

Protestant scholars have recognized that Martin Luther handled James poorly as they have written:

The great reformer Martin Luther...never felt good about the Epistle of James...Luther went to far when he put James in the appendix to the New Testament.

(Radmacher E.D. general editor. The Nelson Study Bible. Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville, 1997, p. 2107)

Martin Luther taught,

Concerning the epistle of St. Jude, no one can deny that it is an extract or copy of St. Peter's second epistle…Therefore, although I value this book, it is an epistle that need not be counted among the chief books which are supposed to lay the foundations of faith (Luther, M. Preface to the Epistles of St. James and St. Jude, 1546).

To me, Jude does not sound that similar to 2 Peter, but if even it is, should it be discounted? Maybe Martin Luther discounted it because it warns people:

...to contend earnestly for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints (Jude 3).

Protestant scholars have recognized that Martin Luther handled James poorly as they have written:

The great reformer Martin Luther...never felt good about the Epistle of James...Luther went to far when he put James in the appendix to the New Testament.

(Radmacher E.D. general editor. The Nelson Study Bible. Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville, 1997, p. 2107)

About this book of the Revelation of John...I miss more than one thing in this book, and it makes me consider it to be neither apostolic nor prophetic…I can in no way detect that the Holy Spirit produced it. Moreover he seems to me to be going much too far when he commends his own book so highly-indeed, more than any of the other sacred books do, though they are much more important-and threatens that if anyone takes away anything from it, God will take away from him, etc. Again, they are supposed to be blessed who keep what is written in this book; and yet no one knows what that is, to say nothing of keeping it. This is just the same as if we did not have the book at all. And there are many far better books available for us to keep…My spirit cannot accommodate itself to this book. For me this is reason enough not to think highly of it: Christ is neither taught nor known in it" (Luther, M. Preface to the Revelation of St. John, 1522).

Furthermore, Martin Luther had little use for the first five books of the Old Testament (sometimes referred to as the Pentateuch):

Of the Pentateuch he says: "We have no wish either to see or hear Moses" (Ibid, p. 202)

Accordingly, it must and dare not be considered a trifling matter but a most serious one to seek counsel against this and to save our souls from the Jews, that is, from the devil and from eternal death. My advice, as I said earlier, is: First, that their synagogues be burned down, and that all who are able toss in sulphur and pitch (Martin Luther (1483-1546): On the Jews and Their Lies, 1543 as quoted from Luther's Works, Volume 47: The Christian in Society IV, (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971). pp 268293).

Original book can be seen here: http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set%5Bmets%5D=http%3A%2F%2Fmdz10.bib-bvb.de%2F~db%2Fmets%2Fbsb00023847_mets.xml

Martin Luther's German Translation of the Bible

The first translation of the Bible into Teutonic (old German) was apparently by Raban Maur, who was born in 776 (O'Hare, p.183). Actually, by 1522 (the year Martin Luther's translation came out) there were at least 14 versions of the Bible in High German and 3 in Low German (ibid).

However, it is true that Martin Luther's translation, became more commonly available, and possibly more understandable (in a sense)--even though it did include his intentional translating errors.

No comments:

Post a Comment